Theodore

M. Vestal, Ph.D.

Professor

of Political Science

Oklahoma

State University

In 1896, Italy, a late-comer to the family of nations and a

slow-footed scrambler for colonial spoils in Africa, made her move to conquer

Ethiopia, the only remaining prize on the continent unclaimed by Europeans.

Expansionist leaders of the recently unified Kingdom of Italy dreamed of a

second Roman Empire, stretching from the Alps to the Equator, and it was

assumed that a show of military would quickly bring “barbarian” lands and

riches into an Africa Orientale Italiana. The Italian dream was turned into a

nightmare, however, in the mountain passes and valleys near the northern

Ethiopian city of Adwa by the knockout punch by the mailed fist of a unified

Greater Ethiopia. The Italians retreated, humiliated. On the other hand, the

battle put Ethiopia on the map of the modern world and had ramifications that

are still being felt today by her own populace and by other African people everywhere.

The preparation of a book to

commemorate the Battle of Adwa provides an appropriate time

to reflect upon the significance of the victory and to attempt to discern any

lessons from that auspicious event that might be of value to present day

Ethiopia and by extension, to Africa and the entire Third World.

A detailed analysis and interpretation of the 1896 episode

and its aftermath would require many books. This section is only a “thumbnail”

picture of Adwa, past and present. The details of the political machinations in

Ethiopia and in Europe and the description of the war itself will be covered in

the next two chapters.

PRELUDE TO THE BATTLE

Italy

entered the Horn of Africa through a window of commercial opportunity. Following

the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, an Italian steamship company, Rubattino,

leased the Port of Assab on the Red Sea from the Sultan of Raheita as a

refueling station. During the next year, Rubattino purchased the port for

$9,440 (a bargain for such a hot property). Rubattino hoped to make money by

controlling the traffic in slavery and arms smuggling.

Meanwhile,

in Europe, the parliament of the newly united Kingdom of Italy met in Rome for

the first time in November 1871. The new government was ambitious and sought

ways to prove its bona fides in the eyes of the world. Colonization of lands

unclaimed by other European powers was viewed as one path to national prestige.

Although Italy coveted African lands across the Mediterranean, it failed in

attempts to occupy Tunisia and Egypt in 1881–1882. Considerations of prestige

were thought to demand expansion somewhere, and imperialists of the time

proclaimed that the “key to the Mediterranean was in the Red Sea” (where

incidentally, there would be less chance of Italy’s clashing with other

European interests).1 Thus, in 1882, the Italian government bought Assab from

Rubattino for $43,200, thereby providing the steamship company a handsome

profit on its investment and unofficially establishing the first Italian colony

in Africa since the days of the Caesars.

Emboldened

by its real estate acquisition on the Red Sea, Italy participated in the

Conference of Berlin in 1884-1885 that “divided up” what was left of Africa

after the initial wave of European colonialism. At the conference, Italy was “awarded”

Ethiopia, and all that remained was for her troops to occupy the prize. This

would take time and cautious expansion from Assab.

To

ensure the safety of its new port, Italy moved to the surrounding interior.

From its Assab base the Italians, through the good office of Britain, occupied

the nearby Red Sea port of Massawa (replacing the Khedive of Egypt, who had

decided he could no longer keep a garrison there) and adjoining lands in 1885.

At that time, the Ethiopian emperor, Yohannes, was distracted by wars in the

highlands and against Sudanese Mahdists who were also battling the British in

the Sudan. After the Mahdi defeated General Charles “Chinese” Gordon at

Khartoum in 1885, the Italians were left as the only Europeans in what they

perceived as a hostile land. The Italian government felt compelled to increase

the military support of its commercial stations.

Emboldened

by their easy occupation of the coastal areas, the Italian army and local

conscripts invaded the highlands in the late 1880s. Italian government leaders

probably overestimated the possible gains in commerce and prestige from this

move. The reputation of Ethiopians as spirited fighters, evidenced in battle

against the Egyptians in the 1870s and against the Mahdists in the 1880s, apparently

was not taken seriously by the Italians. That attitude soon changed when

Ethiopian mettle was tested in the rough terrain of Tigray. After the Italians

provoked some “incidents” on the frontier, their soldiers encountered an Ethiopian

force of 10,000 led by Ras Alula Engeda, Emperor Yohannes’s governor of the

Mereb-Melash, the territory north of the Mereb River and stretching to the Red

Sea — in other words, the land the Italians were occupying. At Dogali, some 500

Italians were trapped and massacred in battle by Alula’s men.

Their

pride wounded, the Italian government moved aggressively in retaliation. Parliament

voted 332 to 40 to increase military appropriations, raised a force of 5,000

men to reinforce existing troops, and attempted to blockade Ethiopia.

To

ease his “Italian problem,” Emperor Yohannes sought the diplomatic help of

Great Britain. As part of the peace diplomacy, Yohannes agreed to give compensation

to the Italians for Dogali and to use Massawa as a trading post. By this time the

French had started building a railroad from Addis Ababa to Djibouti. This would

give Ethiopia a trading outlet on the Red Sea outside Italian influence.

Italian leaders, nursing a sense of shame and a thirst for revenge, decided

something had to be done.

The

man to do it was Francesco Crispi, the prominent leader of the democratic or

radical left wing of the Italian government and the most striking political

personality produced by the new Italy. Eloquent, forcible, and dominating in

Parliament, the Sicilian Crispi served as Prime Minister from 1887-1891 and

again from 1893–1896. A super-patriot, Crispi longed to see his country, that he

always called “my Italy,” strong and flourishing.8 He envisioned Italy as a great

colonial empire, and Crispi’s impulsive hubris would play a vital role in shaping

the events that would unfold in the region. Following the debacle at Dogali,

Crispi told German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck that “duty” would compel him to

revenge. “We cannot stay inactive when the name of Italy is besmirched,” Crispi

asserted. Bismarck is purported to have replied that Italy had a large appetite

but poor teeth. With their military momentum stalled and the bluster of their

milites gloriosi punctured, the Italians, led by Crispi, resorted to guile and

diplomacy to promote their expansionist aims. Taking a page from the British

book of colonial domination, the Italians pursued a policy of divide and

conquer. They provided arms to Ras Mengesha of Tigray and all other chiefs who

were hostile to the Emperor. During his internecine rivalry with Yohannes, even

the Negus of Showa, Menelik, sought closer collaboration with the Italians.

Menelik allegedly welcomed the Italians as allies in a common Christian front

against the Mahdists.

When

the Emperor Yohannes was killed in battle against the Madhists at Metemma in

March 1889, the Italians sensed an opportune moment to solidify their foothold

in the country through negotiation. Count Pietro Antonelli headed a mission to

pay homage to the new Emperor, Menelik II, and to negotiate a treaty with him.

The Treaty of Wuchalé (Uccialli, in Italian), signed in Italian and Amharic

versions in May 1889, ultimately was to provide the raison d’être for the

Battle of Adwa. Under the treaty, the Italians were given title to considerable

real estate in the north in exchange for a loan to Ethiopia of $800,000, half

of which was to be in arms and ammunition. The pièce de resistance for the

Italians, however, was Article XVII, which according to the Italian version

bound Menelik to make all foreign contacts through the agency of Italy. The

Amharic version made such service by the Italians optional. Proudly displaying

the Roman rendition of the treaty in Europe, the Italians proclaimed Ethiopia

to be her protectorate. Crispi ordered the occupation of Asmara, and in January

1890 he announced the existence of Italy’s first official colony, “Eritrea.” To

bolster Italy’s colonial policy, on April 15, 1892, Great Britain recognized

the whole of Ethiopia as a sphere of Italian interest. Italian Prime Minister

Giovanni Giolitti (whose eighteen-month premiership interrupted Crispi’s tenure

in the office) affirmed that “Ethiopia would remain within the orbit of Italian

influence and that an external protectorate would be maintained over

Menelik.”11 The Ethiopians were not too concerned with such Italian braggadocio

until 1893, when Menelik denounced the Wuchalé treaty and all foreign claims to

his dominions and attempted to make treaties with Russia, Germany, and Turkey.

In a display of integrity rare among belligerent nations, Menelik paid back the

loan incurred under the treaty with three times the stipulated interest. He

kept the military equipment, however, and sought to rally the nation against a

foreign invader.12 The Italians railed at this insubordination by a “Black

African barbarian chieftain,” and prepared to go to war to teach the Ethiopians

a lesson in obedience.

Having

claimed a protectorate, Italy could not back down without losing face.13

Crispi, under fire at home from both conservatives and the extreme left bloc of

Parliament for his “megalomania,” may have seen victory in Africa as his last

chance for political success. From his perspective, a colonial war would be good

for Italy’s (and his) prestige and Crispi envisioned a protectorate over all of

Ethiopia. General Antonio Baldissera, the military commander at Massawa, had a

more modest goal — the permanent occupation of Tigray. The Italian Deputies would

have been content with a peaceful commercial colony. With such occluded aims,

the African campaign suffered generally from a lack of will among Italians in

the homeland.

While

the Italians massed arms and men in their Colonia Eritrea, their agents sought

to subvert Ethiopian Rases and other regional leaders against the Emperor. What

the Italians did not realize was that they were entering into the Ethiopian

national pastime: the tradition of personal advancement through intrigue.16

Menelik, master of the sport, trumped the Italians’ efforts by persuading the

provincial rulers that the outsiders’ threat was of such serious nature that

they had to combine against it and not seek to exploit it to their own ends.

The Emperor called his countrymen’s attention to the fate of other African nations

that had fallen under the yoke of colonialism. The magic of Menelik worked.

Whatever seeds of discord the Italians had planted sprouted as shoots of accord

on the other side. Meanwhile, Italy carried out further intrusions into

Ethiopia. On December 20, 1893, Italian forces drove 10,000 Mahdists from

Agordat in the first decisive victory ever won by Europeans over the Sudanese

revolutionaries and “the first victory of any kind yet won by an army of the

Kingdom of Italy against anybody.”17 Flushed with success on the battlefield,

the Italian populace embraced new national heroes, the Bersagliere, soldiers of

the crack corps of the Italian

army. The Bersagliere, depicted in the press wearing “a pith helmet adorned

with black plumes, facing a savage enemy on an exotic terrain,” appealed

to the passionate patriotism of the masses and to the romantic adventurism of

young men. Enthusiastic conscripts responded to the call to the colors. The

belligerent Italians soon mounted the strongest colonial expeditionary force

that Africa had known up to that time. The Governor of Eritrea, General Oreste

Baratieri, had about 30,000 Italian troops and 15,000 native Askaris under his

command (Great Britain would surpass that number a few years later when 250,000

troops would be sent to South Africa during the Boer War). Secure in his

new military strength, Baratieri again went after the Mahdists. On July 12, 1894,

his forces drove the Dervishes from Kassala, killing 2,600 while losing only 28

Italian dead — the most one-sided victory won by Europeans over the Mahdists. The

Italians were not doing so well on the diplomatic front, however. In July

1894, Russia had denounced the Treaty of Wuchalé. An Ethiopian mission was

received in St. Petersburg “with honors more lavish than those accorded any previous

foreign visitors in Russian history.” To add injury to diplomatic insult, Tsar

Nicholas sent Ethiopia more rifles and ammunition.

In 1895, Baratieri followed up his

victory over the Dervishes with another successful offence at Debre Aila

against an Ethiopian force larger than his own, under the command of Ras

Mengesha. The Italians drove out the ruler of Tigray and prepared for a

permanent occupation of his land. Other minor military actions of the Italians

in 1895 fuelled the anger of the Ethiopian masses and leaders alike, who viewed

the invasion as a threat to their nation’s sovereignty.

Emperor

Menelik’s reforms had transformed the economy and improved the tax base of the

country enabling him, as never before, to raise and equip armies.20 In the

highlands, Menelik massed his troops and marched north to meet the Italian aggressors.

In December, an Ethiopian army of 30,000 trapped 2,450 Italian troops at Amba

Alaghe, the southernmost point of Italian penetration. In the ensuing battle,

1,320 Italians were killed or taken prisoner. At the same time,

Ethiopians

laid seize to a formidable Italian fort at Mekele. Menelik, perhaps still

hoping to settle his conflict with the Italians peacefully, negotiated a

settlement whereby the besieged were evacuated and allowed to join their

compatriots. These events infuriated Crispi, who taunted his commanders for

their incapacity and cowardice. He called the Ethiopians “rebels” who somehow

owed allegiance to Italy. Although the opposition in parliament led by Giolitti

criticized the government for providing inadequate food, clothing, medical

supplies, and arms to the troops, Crispi was able to garner additional military

appropriations by claiming that the troop movements were purely defensive. He

assured parliament that the war in Ethiopia would be a profitable investment.

THE

BATTLE OF ADWA

By

late February 1896, the Italian army was entrenched around Mount Enticho in

Tigray. Led by General Baratieri, who was just back from Rome (where he had

been awarded the “Order of the Red Eagle”),23 the 20,000 Italians and

Italian-officered native auxiliaries had waited for the Ethiopians to attack their

fortified positions as they had done in previous battles. When such an attack

did not occur, Baratieri ordered what he hoped would be a surprise attack on

the Ethiopians assembled near Adwa. Defeat was unthinkable for a modern European

army of such size with its disciplined and well-equipped formations. A decisive

victory over the upstart natives would win a vast new empire for Italy.24

Unfortunately for Baratieri, he was maneuvering over unfamiliar terrain without

accurate maps, relying upon ineffective intelligence, and leading troops garbed

in uniforms designed for European winters a disastrous combination of

ingredients.

Awaiting

the Italians was a massive Ethiopian army, 100,000 men strong, with contingents

from almost every region and ethnic group of the country. They were commanded

by an all-star team of warriors amassed by Menelik in “an eloquent demonstration

of national unity.” About two-thirds of

the troops raised as part of national mobilization were recruited under the

Gibir-Maderia system, a non-monetarized form of payment of land grants and food

and drink to the soldiers from tenants working the land. The Emperor and

Empress mobilized about 41,000 troops while the governors-general and regional

princes raised most of the others. When the Italian troops made a three-column

advance against Ethiopian positions on March 1, St. George’s Day, the combined

forces of Greater Ethiopia were primed for a fight. The Ethiopians surrounded

the Italian units and in fierce combat, closed with and destroyed many of the

enemy in the bloodiest of all colonial battles. Peasant troops fought

ruthlessly and a large number of Ethiopian women, following the example of the

“Warrior Queen,” Empress Taytu, were on the battlefield. They served as a water

brigade for the fighting men, paramedics, and guards of prisoners. The Italians

inflicted heavy casualties upon their attackers. The artillery crews were especially

noteworthy in firing their cannons as long as they could and defending their

positions until they were all killed. But the main Italian force and its

supplies were caught in Menelik’s strategic trap and were hammered by Ethiopian

infantry and artillery in a place of their choosing. At the end of the day, the

Italians had suffered one of the greatest single disasters in European colonial

history (the British lost more men in Afghanistan; the Spanish were to leave

12,000 dead on the field in Morocco in 1921). There were 11,000 dead from both

sides, including 4,000 Italian soldiers. In one day nearly as many Italians

lost their lives as in all wars of Risorgimento put together. Remnants of the

Italian army retreated northward, leaving behind 1,900 Italian and 1,000

Eritrean askari prisoners of war. In addition, the Ethiopians captured four

million cartridges and fifty-six cannon. Menelik chose not to pursue the routed

army. With the battle over, he held a religious service of thanksgiving and

proclaimed a three-day period of national mourning. The victory celebration of

the jubilant Ethiopians was muted because the Emperor saw no cause to rejoice

over the death of so many Christian men.

The

military advantage won by Menelik was not followed up politically. Why he did

not press his advantage and drive the foreigners from his country remains a

puzzle. The Emperor may have been concerned about consolidating his territorial

interests in the south and may have been afraid of over-extending his

resources. At the time, the kingdom was beset with famine and internecine quarrels.

Whatever his reasons, Menelik allowed the Italians to remain in their colonial

foothold in Eritrea, creating what was to be a continuous source of problems

for Ethiopia ever since. He also missed a golden opportunity to guarantee Ethiopia

an outlet to the sea. What Menelik had demonstrated, however, was that he had

the power to defy any European imperialists. The defeat at Adwa brought Italy

its greatest humiliation since unification and genuinely demoralized the

Italian public. Their string of relatively easy colonial victories, the first

their army had attained, came to an abrupt and shocking end. Political leaders

had not prepared the populace for defeat in Africa, let alone a total disaster.34

“All is saved except honor” proclaimed the Tribuna. Stunned crowds outside of

Parliament shouted, cheered, cursed, hissed, howled, and groaned.36 Some were

heard to cry, “Long live Menelik!” All available Italian transport steamers

were ordered to assemble at Naples “to take troops to Massawa.” It was rumored

that Baratieri planned a military coup to rehabilitate his reputation, before

Baldissera superseded him. Church fathers were described as being delighted at

the failure of the “Satanic” Italian armies that had paid the wages of a divine

vendetta at Adwa.39 The Pope was so disturbed by the news that he cancelled a

Te Deum and a diplomatic banquet in celebration of the anniversary of his

coronation. A shameful scar had been inflicted on the nation one that would

fester for forty years41 until Mussolini would pour his snake oil over it. Crispi’s

political career was shattered as was the nation’s colonial ambition that he had

come to personify.42 Hailed as the greatest parliamentary statesman of Italy,

the seventy-seven year old Prime Minister was recognized as one of the chief

political figures of Europe.43 Crispi was acclaimed as the most important

Italian and was the only Premier who really captured the nation’s imagination.

His impulsiveness marred his career, and his actions all too often were “neither

informed by knowledge nor controlled by sound judgment.” His ideas were

grandiose beyond the resources of the country.44 As the New York Times

editorialized, “his greatest mistake [was] in supposing the attention of the Italian

people could be successfully diverted from domestic scandals by foreign embroilments.

In

June, General Baratieri was brought to trial and, although he was acquitted, it

was “in terms that branded him with incapacity.”46 With all Italian troops

withdrawn from Tigray and reassembled in Eritrea, General Baldissera defended

the colony and drove the Dervishes away from Mount Mocram a month after Adwa.

The Italians killed 800 of the invading force of 5,000 and in short order won a

brisk series of skirmishes with the Mahdists.47 In 1897, Kassala was ceded to

Great Britain, and during the following year, forces under the British general

Horatio Kitchener defeated the Mahdists in a decisive battle at Omdurman. In

the United States, newspaper reporting generally was not sympathetic to the

Italian cause. The New York Times ran front-page stories with consecutive day

headlines heralding “Italy’s Terrible Defeat,” “Italy is Awe-Struck,” “Italy

Like Pandemonium,” and “Italy’s Wrathful Mobs.”48 An editorial on

March

5, 1896, opined, “The Italian invasion of Abyssinia…was a mere piece of piracy…an

enterprise unrighteous. In truth, the Italian ‘colonial expansion’…is not

founded on fact or reason, and has nothing to say for itself in the form of morals

and of civilization. It is no more businesslike than it is moral…It is not on business

but for glory that they go to war.”49

THE

SIGNIFICANCE OF THE BATTLE

For

the victor, the rewards were immediate and long lasting. In the negotiated peace

following the battle, the Treaty of Wuchalé was annulled, ending Italy’s

self-proclaimed “protectorate” over Ethiopia. The settlement acknowledged the

full sovereignty and independence of Ethiopia. The Italians paid an indemnity

of $5 million in gold; but they were allowed to remain in Eritrea. The price

paid by Italy for its belated quest for empire was extravagant in terms of money,

lives, arms, and prestige at home and abroad. Eritrea, instead of paying for

itself, devoured money. The Red Sea evidently was not a key to the

Mediterranean, 50 and the Italians’ zest for empire had disappeared for the

moment. It would not be until 1911-1912 that Italian agents of imperialism

would again venture into Africa in the Libyan War and begin the colonial

activity described

as

“the collecting of deserts.”

By

winning the battle, Menelik had preserved and extended the territories of

ancient Ethiopia — with the important exception of Eritrea. By uniting most of

the leaders from almost all parts of the country against a common foe, the Emperor

began to implement the idea of a central government that might supplant the

Ethiopian Orthodox Church as the symbol of national unity. Thus, the battle

gave momentum to the creation of the modern Ethiopian empire-state, and the

future of Ethiopia diverged from that of the rest of Africa.

Internationally,

Ethiopia supplied the most meaningful negation to the sweeping tide of colonial

domination of Africa. Egged on by Italy’s defeat, European nations rushed to

conclude treaties with Menelik’s government. Indeed, 1896 became the “year of

the ferenj” in Ethiopia. Expatriate traders flocked in and spearheaded the acceleration

of economic activities. In record numbers, European governments set up

consulates throughout the country and aided foreign merchants and investors in

seeking concessions and royalties. Menelik’s retaining the defeated Italians as

good neighbors had positive results: “aspirations of the peaceful penetration

school of imperialism and of the more narrowly based small traders on the Red

Sea were a major factor in influencing the nature and direction of Italian

imperialism that served both as a counterweight and an alternative to the

designs of more militant expansionists.” major benefit also accruing to

Ethiopia at that time was the introduction of European medical practices.56 Shortly

after the battle, Menelik applied for Ethiopia’s admission into the Red Cross

Society, another sign of acceptance into the family of nations. In addition to

material changes, the Battle of Adwa produced psychic rewards. Ethiopians

basked in national pride and a sense of independence, some say even superiority,

that was lost to other Africans mired in the abasement of colonialism.58 This

post-Adwa spirit of Ethiopia, instilled in successive generations, gave

Ethiopians a confidence and a unique Weltanschauung. The image of independent

Ethiopia, the nation that successfully stood up against the Europeans, gave

inspiration and hope to Africans and African-Americans fettered by racial

discrimination and apartheid in whatever guise. Ethiopia provided a model of independence

and dignity for people everywhere seeking independence from colonial servitude.

LESSONS

FROM THE BATTLE

One

hundred plus years after the Battle of Adwa, Ethiopia faces an internal threat

to its people’s dignity from a government dominated by Marxist-Leninist ideology

intent on dividing the nation along ethnic lines. There is little danger from

external sources, although it can be argued cogently that the EPRDF-led government

remains in power only by being propped up by developmental financial assistance

from donor nations. As in 1896, the danger to Ethiopia originates in the

mountain passes and valleys of Tigray and Eritrea. Although the artificial

administrative border drawn between Eritrea and Tigray by the Italians is now

proclaimed to be the boundary of sovereign nations, it remains an artificial

creation, for the people on both sides of the frontier are one in race and

civilization.60 Both are indeed part of Greater Ethiopia. In a similar fashion,

the boundaries of the EPRDF administrative region drawn along ethnic lines

ignore historic ties between areas that transcend linguistics and lineage. Both

the EPRDF and the EPLF (now PFDJ)61 should ponder an episode of the battle of

Adwa: as a result of faulty map reading (or a faulty map), an Italian brigade

found itself isolated and the target of the combined fury of the Ethiopian

troops.62 Cartographic misjudgments may haunt their makers.

That

is exactly what happened in May 1998, when Eritreans, using faulty maps, threw

down the gauntlet before Ethiopia in the Badme triangle. The ensuing slaughter

and human suffering in the two-year war that followed was a curse upon both

nations.63 The ruling Ethiopian party, whose leaders had denigrated the history

of the Battle of Adwa and its uniting of the people of Greater Ethiopia,

suddenly recovered its memory and sent young volunteers off to fight the

invading Eritreans with songs and dances recalling that defining moment in the

nation’s past. By June 2000, the Ethiopians had won the war, and the two

nations signed a ceasefire agreement which provided for a UN observer force to

monitor the truce. This was followed in December by Ethiopia and Eritrea

signing the Algeria Peace Agreement, formally ending the conflict. The

agreement established the Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission (EEBC) to

delineate the disputed border. The boundary commission’s decisions were

supposed to be binding on both sides. In April 2002, however, the EEBC ruled

that the disputed town of Badme was in Eritrea, and Ethiopia found the ruling

unacceptable. Once again, cartography ignited hostilities in the Horn, and the

armies of the two neighbors glared menacingly at each other across a

twenty-five kilometer-wide UN-monitored buffer zone.

The

right of “nationalities” to secede from Ethiopia (proclaimed in Article 39 of

the Constitution of the FDRE) may be a paraphrase of European rhetoric, but the

roots of the problem of secession have their origins in the creation of the Italian

colony in the late nineteenth century. One can only speculate about the different

course Ethiopian history might have taken had Emperor Menelik dispelled the

Italians from the land of the Habesha. Like the Italians under Baratieri, the

present government seeks to divide and conquer its opposition. Some leaders of

the political opposition have taken the bait and succumbed to the old national

pastime of seeking personal advancement through intrigue. Although the TPLF and

EPRDF applaud their efforts, most Ethiopians who want real democracy in their

country have grown tired of demagogues’ games. In the May 2005 elections,

opposition leaders agreed to combine forces to oppose the divisive ethnic

politics and the deficits of democracy of the EPRDF regime. This was a

significant event, but missing from the election fray was a Menelik of today to

ignite a national flame uniting peasants and metropolitans from every

background and from every part of the country against a common foe and for the

good of Ethiopia. Present in 2005, however, were today’s Taytus, “warrior

queens,” exhorting the opposition to strive for victory. The legacy of the

Battle of Adwa is a powerful beacon for the inheritors of an independent and

proud Ethiopia. Can its light lead all Ethiopians to come together to bring the

blessings of democracy to their homeland? In 1896, increased Italian military

action steadily aroused the nationalism of Ethiopia and the chances of

exploiting her feudalism and dividing her nobles was correspondingly

diminished.64 Today, one sees signs that heavy-handed government repressions

have steadily aroused Ethiopians’ spirit of nationalism and the chances of

exploiting ethnicity and dividing the country will correspondingly be

diminished.

Perhaps

Emperor Menelik captured best the spirit that might motivate all freedom loving

Ethiopians to get involved in efforts to bring democracy to their homeland by

peaceful means. In a wax- and gold-laden statement, just as pertinent now as it

was over a century ago, said Menelik: “If powers at a distance come forward to

partition Ethiopia between them, I do not intend to be an indifferent spectator.” Ethiopians are no longer limited to their highland fortress on the Horn of

Africa; they are part and parcel of a globalized world that recognizes sovereignty

a value for which the heroes of Adwa sacrificed their lives.

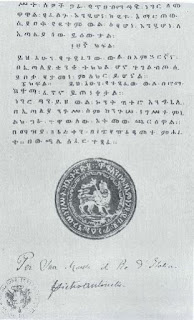

AMHARIC VERSION OF THE WUCHALÉ TREATY

0 Comments